2007 CNTL TIME : SoYoun Jeong _ Hyewon Yi

CNTL TIME : SoYoun Jeong

Hyewon Yi

SoYoun Jeong (born in Seoul, 1967) studied painting at Ewha Womans University. Gradually Jeong’s interest shifted to new media such as video, where she found possibilities for playfully manipulating time and virtual space. Often described as an “off-genre artist,” Jeong uses diverse media ranging from video to sculpture to installation. In the exhibition CNTL TIME, she examines disappearance of technology and human beings, motions in everyday life, the repetitive tasks of a mother, and the issue of reality versus simulation.

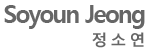

Changing Images: Copy Using Analogical Method – Breathe,

8-channel video installation with 8 monitors, 2000.

Controlling time, which video art can do better than any static medium, is what distinguishes Jeong’s work. Time is most metaphorically visible in Changing Images: Copy Using Analogical Method – Breathe. There Jeong focuses on an analogue technology that is disappearing fast in the digital era. When videotapes are copied repeatedly, their images progressively decompose and fade. Jeong begins by capturing footage of her dying grandparents, who undergo heavy breathing before the end of their lives. A clearly visible image of the dying grandparent in the first TV monitor gradually transforms into a coarse-surfaced depiction and finally flickering images and streaks. Colors lose their brilliance, and the descriptive image becomes abstract. At a time when everyone is able to share unlimited digital data, at will, through websites like youtube.com, Jeong harks back to the confining and cumbersome materiality of analogue that wears out just as people do. Breathe thus refers not only to a disappearing technology that once saw wide usage, but also disappearing human existence. It is Jeong’s way of delivering a dual “memento mori.” Breathe conveys the certainty of mortality of one from of technology and of all human lives.

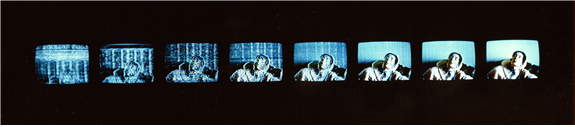

Narcissism, 1-channel video installation with liquid crystal monitors,

mirror glass, wood, and DVD player, 1999.

A sustained record of the artist washing her own face is introduced in Narcissism. Viewers are confronted with a distorted image of a woman whose face appears and fades through the undulating wave of water, resulting in an amusingly surrealistic effect. On the surface of the mirror glass installation, the reflection of the viewer’s own image is superimposed upon the artist’s face, complicating the visual experience. Narcissism explores the issue of conscious/unconscious seeing and being. A similar theme is also reflected in work The Eye to See Desire, where an enlarged eye constantly blinks and gazes at the viewer.

Ordinary actions, like those in Narcissism, are further scrutinized in the video installation Welcome to My House, this time through fast-forwarded sequences that show the artist raising a son in her New York apartment. In these compacted time studies of Jeong’s daily life at home, the viewer witnesses the lively repetitive tasks of a mother as well as the fast-paced motion of an urban dweller (which can be also seen in another work for this show, Two Existences within Me). This two-channel video, showing both the inside and outside of the apartment, presents her living quarters as a virtual stage, displaying her private life in the space of art gallery. It is a work of self-surveillance; the video camera is reflected on the window of the apartment. Documenting her everyday life and even revealing the dying moments of her own grandparents, the artist raises ethical questions about visual monitoring and exposure at a time when video cameras are becoming ubiquitous.

Welcome to My House, 2-channel video projection with 2 glasses, 2005-06.

The theme of virtual representation that Jeong examines in Welcome to My House is further explored in two sculptural installations, Collecting Specimens and Would You Like Some Dessert?

Inspired by her son’s toys, Jeong creates effigies of animal characters that remind us of insect specimens. Her child, raised in cities like Seoul and New York, has experienced animals primarily through television images like that of Mickey Mouse. Among urban children weaned on mass media, collecting these mascots has indeed replaced collecting real specimens of butterflies, moths, and insects. Children in the electronic age understand the real world through these substitute “simulacra.” Jeong petrifies images of Mickey, Minnie, Goofy, and Donald in terra-cotta and white porcelain.

Left, Mickey Mouse from a series “Collecting Specimens,” terra-cotta, 33.5 x 33.5 x 3.1 inches, 2002.

Right, Would You Like Some Dessert?, gilded plates, imitation pearls, cubics, spangles and other decoration goods, transparent silicone, each plate 16 inches in diameter, 2007.

The representation of reality through simulated objects is further explored in Would You Like Some Desert?, multiple golden dessert plates adorned with transparent and sparkling fake jewelries. These artificial plates are critiques of the so-called “Room Salon” culture in Korea, where Korean men can drink alcohol and enjoy such lavishly decorated desserts, along with equally embellished women whose service goes beyond pouring the alcohol. The details of the Korean “Room Salon” culture, which is largely unknown to most Korean women due to its exclusivity, can now be imagined through Jeong’s simulacrum sculptures. By mimicking and multiplying the presentation of these uneatable frivolous objects, Jeong emphasizes the hollowness and superficiality of this gender-specific consumer culture where women’s sexuality becomes largely a selling point. The repetitive aspect of this work recalls Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1961-62), while the overall feminist context and the configuration of plates with variously crafted details remind us of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1979).